Use our convenient online scheduler to book an appointment now.

You’ve never had pain in your shoulder before. Then you had a subtle injury. It wasn’t even that bad. But you are very uncomfortable, and you can barely lift your arm. Your doctor told you that you have a large and very old rotator cuff tear. You were also informed that the tear is no longer fixable. How can that be possible? Well, unfortunately, it can, and you’re not alone. This type of problem is more common than you might imagine, and nearly everyone who’s been told they have an irreparable rotator cuff tear wonders the same things.

So, let’s take a closer look.

What Is An Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tear?

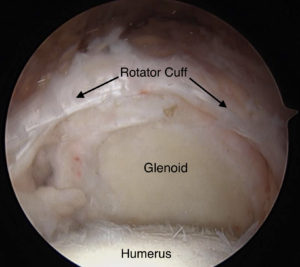

You may recall from other posts that the rotator cuff is a group (a “cuff”) of four tendons deep in your shoulder. These tendons begin as muscles on your shoulder blade and end as an aggregate of tendons on the top of your upper arm (humerus). When you attempt to move your shoulder, you are contracting, or shortening, the muscles attached to these tendons. When the muscles shorten, they pull on the tendon at its bone attachment, which then moves your arm at your shoulder.

The four tendons attach to the humerus in different locations, and so depending on which muscles you engage, your shoulder will move in different directions. There are two tendons on the top of your humerus, the supraspinatus and the infraspinatus, one rotator cuff tendon in the front of your shoulder, the subscapularis, and one in the back, the teres minor.

The shoulder is very complicated. As a result, even simple shoulder motions require well-coordinated muscle, tendon, and bone interactions.

The most common rotator cuff tendons to tear are those on the top of your humerus, the supra- and infraspinatus. Of the two, the supraspinatus tears much more often. Frequently, they may tear together.

How do these tears occur?

This isn’t always clear. Some times the rotator cuff tears from acute trauma. However, the tears that occur without symptoms over time are most often not traumatic. Or at least not acutely traumatic. These tears tend to happen slowly, over time, as a result of microtrauma and intrinsic changes to the tendon. These tendons have an inadequate blood supply as well as other age-related biologic impairments that adversely affect the tendon’s ability to heal damage. As a result, because the tendon healing is impaired, damage accumulates with age and time, until the tendon fails and pulls off the bone.

Over time, the tear can increase in size due to persistent tension in the attached muscle. This tension pulls the torn tendon further away from its previous attachment. In addition, because the tendon is no longer attached to the bone, as the muscle contracts, there is very little if any resistance. Just as with all of our muscles and tendons, these particular muscles and tendons need to work against resistance to maintain their strength and form. Without resistance, the muscles and tendons atrophy. When this occurs, not only does the tendon get thinner and weaker, but it also gets shorter. This enlarges the tear even further.

All of this, the enlarged tear, the muscle and tendon atrophy and the lengthy time since failure, frequently leading to a very large tear, often involving multiple tendons that are of poor quality and quantity and are attached to muscles that are weakened, atrophied, shortened and scarred, result in an irreparable rotator cuff tear.

Additionally, as if that isn’t enough, if this process continues, bony changes to the shoulder joint can also develop.

Rotator Cuff Arthropathy

As the tendons on the top of the humerus fail and retract away from the humerus, one of the major supports keeping the humerus in place and centered on the glenoid is lost. In the normal shoulder, as you attempt to lift your arm, you contract your rotator cuff and your deltoid. Your deltoid also attaches to the side of your humerus but lower down your arm than your cuff. When the deltoid contracts, it attempts to elevate your humerus. In the intact shoulder, since the rotator cuff is present on top of the humerus, the humerus is held centered on the glenoid and rotates in place, rather than elevating. This results in your arm rising overhead, rather than your humerus rising to the undersurface of your acromion.

However when, there is no adequate superior cuff, the deltoid contracts and elevates your humerus. As a result, your humerus migrates proximally, often to the undersurface of the acromion. When this occurs, the humerus and glenoid are not aligned. Just as if the tires on your car are not aligned, if the bones at a joint are out of alignment, the surfaces will wear prematurely. This wear results in changes to the bone and a loss of cartilage at the joint. These changes are known as arthritis, or arthropathy. When arthritis occurs due to rotator cuff deficiency, it is called rotator cuff arthropathy.

The issue…

Many people can walk around with their shoulder in this condition and have absolutely no symptoms.

How is this possible?

It’s not completely clear…

Most likely, the tear occurs so slowly that it enables the accessory muscles of your shoulder to slowly accommodate to the progressing rotator cuff deficiency. It’s often when something changes abruptly, that symptoms and dysfunction develop. Often this follows an injury. The injury could be significant or subtle. Sometimes, the symptoms occur without any apparent cause. It may be that the tear has abruptly increased in size. Possibly a relatively acute onset of weakness occurs to an already tenuous situation either from overuse or an injury. It may be that joint swelling from an injury, or other causes of inflammation, develops. Or perhaps, if there is an injury, the symptoms may result from the pain and subsequent stiffness that can occur. Some or all of these may be responsible for the sudden increase in pain and dysfunction.

Nonetheless, no matter the cause, when this occurs, it is a significant problem. It is not uncommon for patients who have had no apparent issues with their shoulder previously to come into the office with a complete inability to elevate their arm. We call this pseudoparalysis. Yesterday they were functioning fine without any problems. Today they are in severe pain and can’t move their arm.

Your Free Guide To Shoulder Injuries, Pain, Treatment & Prevention

What to do?

The options are limited. The rotator cuff is likely no longer repairable. Even if repair is possible, there is a great chance that the repair will fail due to the inferior status of the tendons. If there is rotator cuff arthropathy, this is an even bigger problem.

Although this sounds hopeless, options do exist – both nonsurgical and surgical treatments. We will discuss these in a later post.

Join our Mailing List

TCO provides patients with orthopedic problems the trusted resources and patient-centered advice they need to “Feel Better. Move Better. Be Better.”

© 2024 Town Center Orthopaedics | All Rights Reserved